I gave a talk at the Optic Nerve Meeting 2024, Obergurgl, Austria, 10-12 December 2024. The title was:

« Foveal Ganglion Cell characteristics in fast flying birds hunting on the wing »

Authors: Tania Rodrigues, Michel M. Matter, Alain Chiodini, Bernard Genton, Emilie Brethaut, Lidia Matter-Sadzinski and Jean-Marc Matter

Purpose

The amount of information gathered and the speed of the exchange of information between different brain regions are considered to be the major evolutionary path to high cognitive power in amniotes. Notably, they are a major driving force behind evolution of the bird brain. In this respect, the study of the nervous system of fast flying birds that coordinates vision and movement is a rich source of inspiration and insight.

The Swift and the Swallow

The Barn Swallows (Hirundo rustica) and the Common Swifts (Apus apus) are fast flying birds known from everyone but often confused. These unrelated species are separated by millions of years of evolution, yet they use the same strategy for tracking, identifying and catching insects on the wing. They are able to catch one insect every 5 to 10 seconds, while flying at 40 to 60 km/h. Few vertebrates are able to achieve this feat.

One might think that swifts and swallows chose preys at random, but this is not the case. Bolus analysis revealed that they are able to identify insects according to their size, shape and colors. For instance, they can make the difference between black and yellow flying ants. Surprisingly, despite their exceptional sensory-motor response, their visual systems have received little attention.

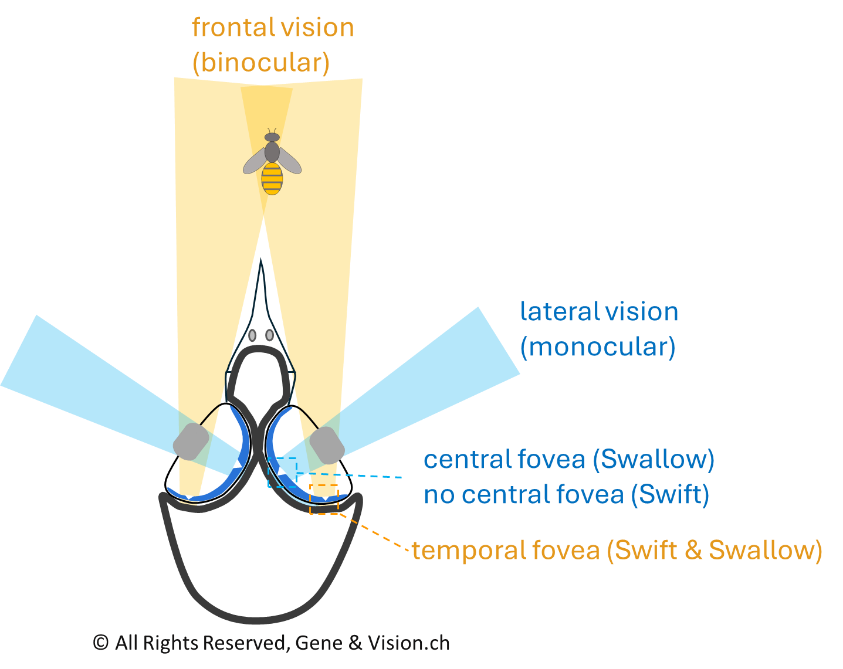

When a swift or a swallow is about to catch an insect passing through its frontal visual field (Figure 1), the image moves instantly across the temporal fovea and the bird has less than 50 milliseconds to identify this insect and decide whether to catch it. In addition, it must adjust flight so that the insect is close to its open beak. How is the temporal fovea designed to enable the bird to achieve this highly challenging task?

The swift vs. the swallow retinae

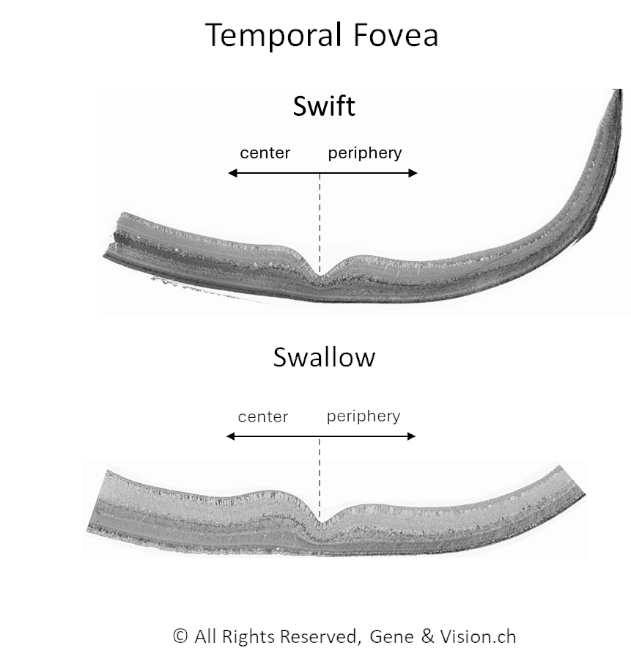

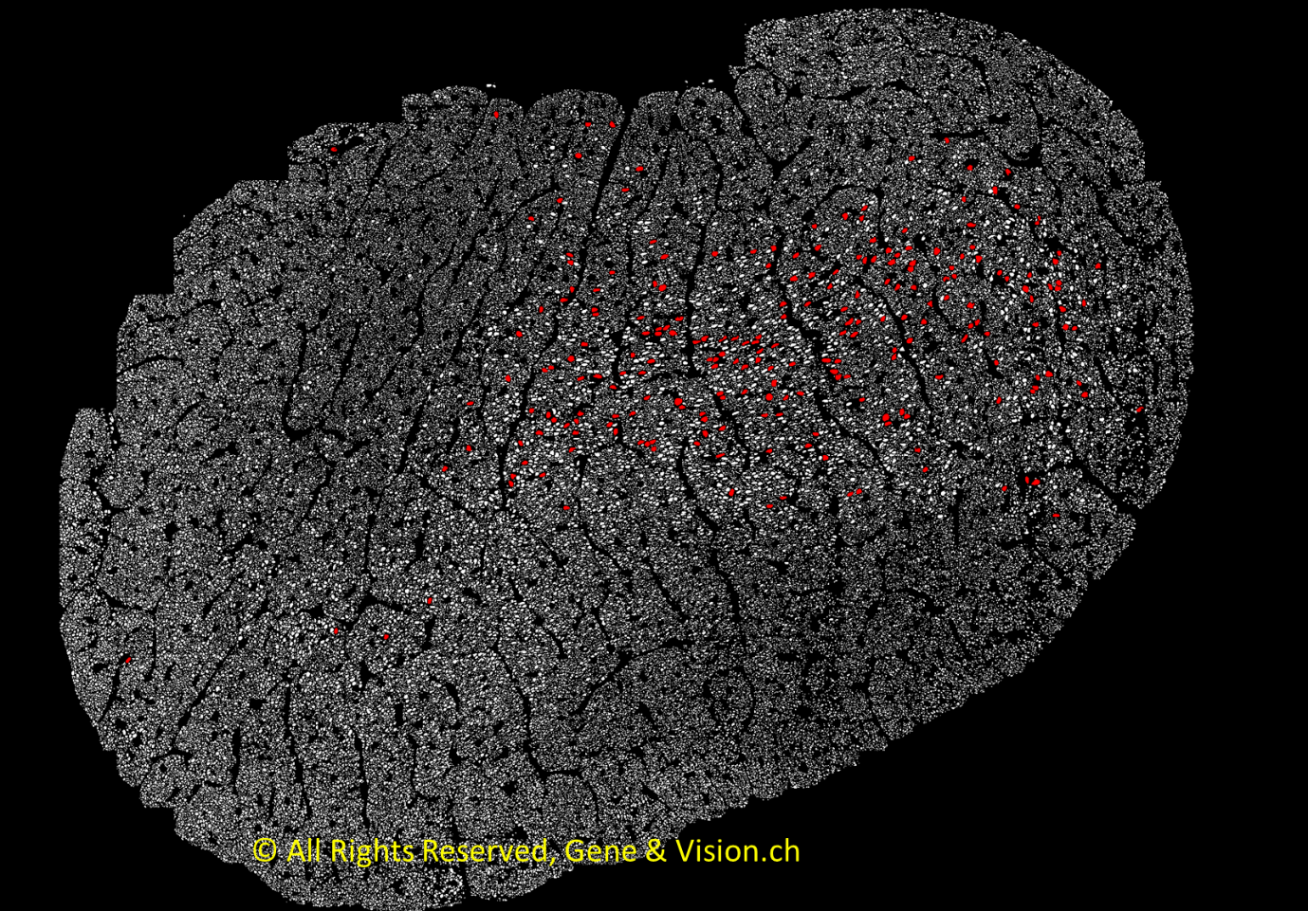

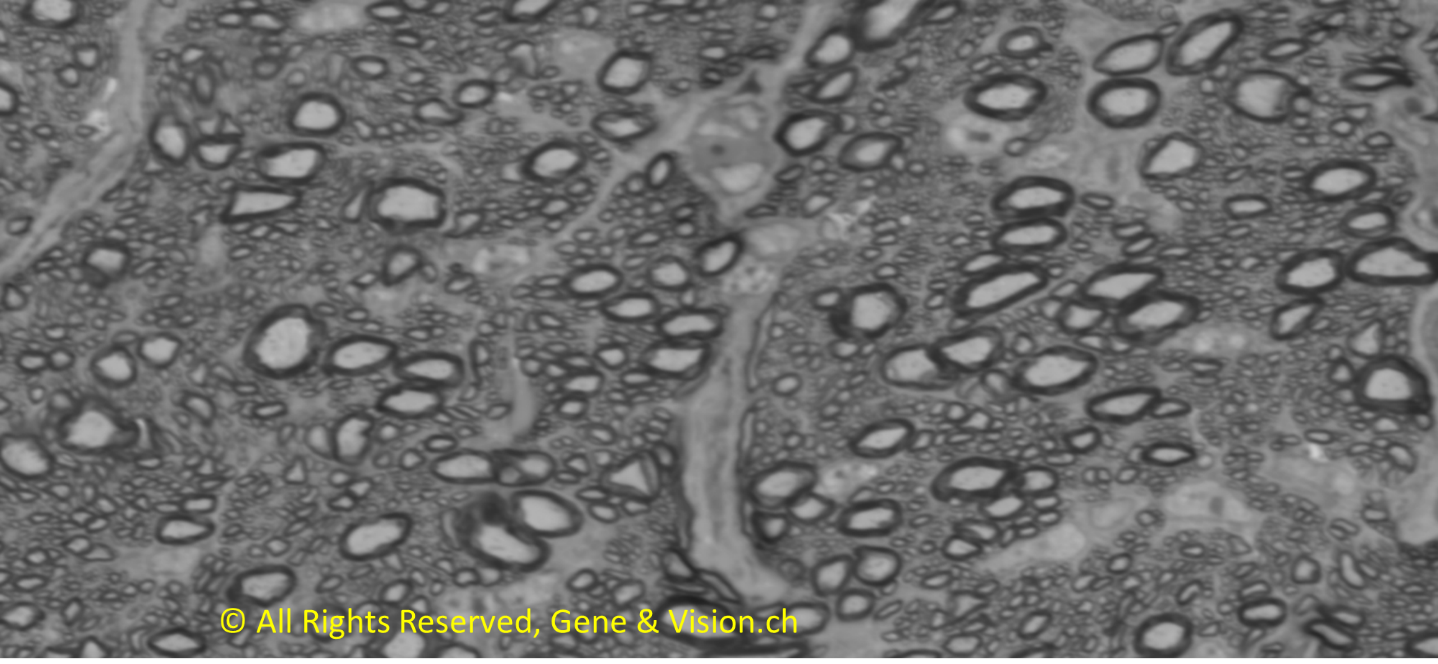

Despite the fact that the swifts and swallows display similar behaviors, their retinae are in many respects different. The most striking difference is the presence of a central fovea in swallows, while swifts lack it (Rochon-Duvigneaud, 1943; Oehme, 1962; Rodrigues et al. 2023). The differences that distinguish the two species go beyond the central area. Indeed, most of their retinas have a different microanatomy. In swift, the number and ratio of neurons are basically the same over the whole retina, while this is not the case in swallows. Such big difference between birds that exhibit basically the same behavior seems to be at odd with the view of the evolution of the eye and the retina as being ‘task-led’. However, despite these major differences, both species have a temporal fovea with a deep pit (Figure 2).

These temporal foveae are almost identical and have the particularity of being asymmetric, i.e., the microanatomy of the fovea oriented towards the periphery is different from the one facing the center. The fact that basically the same fovea can develop in retinas, which, on the whole, are different, challenge our current understanding of how retinogenesis proceeds.

This special fovea, which could possibly develop with some autonomy, might be the only option for fast flying birds hunting on the wing.

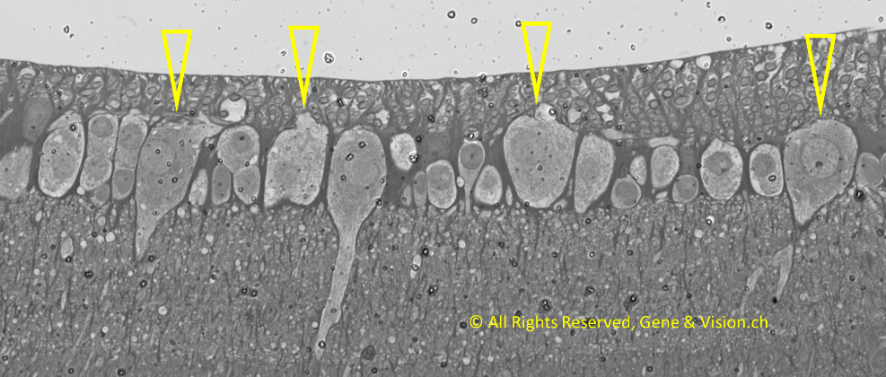

Big Ganglion Cells feature the swift and swallow temporal foveae

In the foveal area, they are clusters of big Ganglion Cells with somata larger than 250 μm2 (Figure 3). They were not identified in other retinal areas.

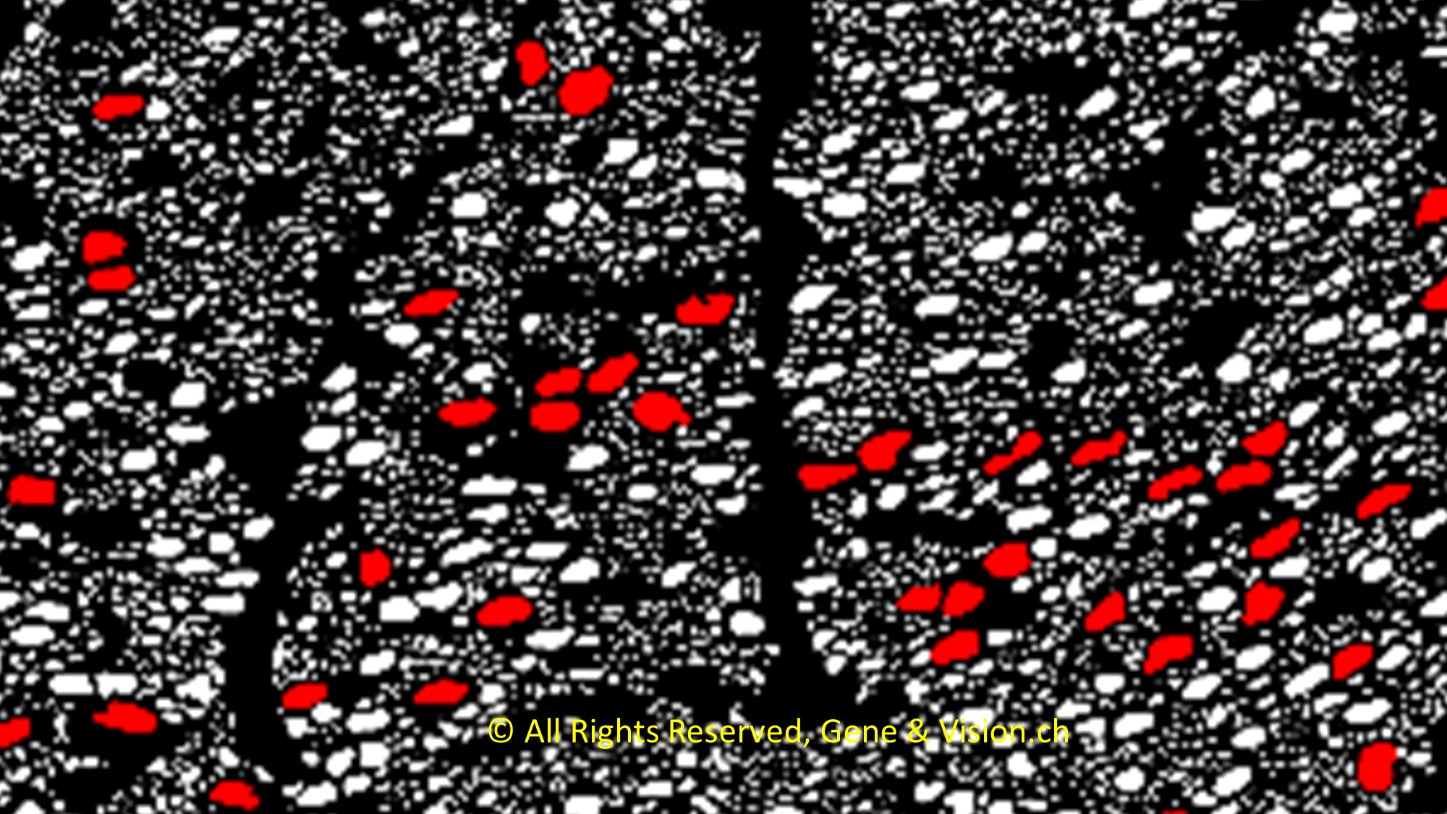

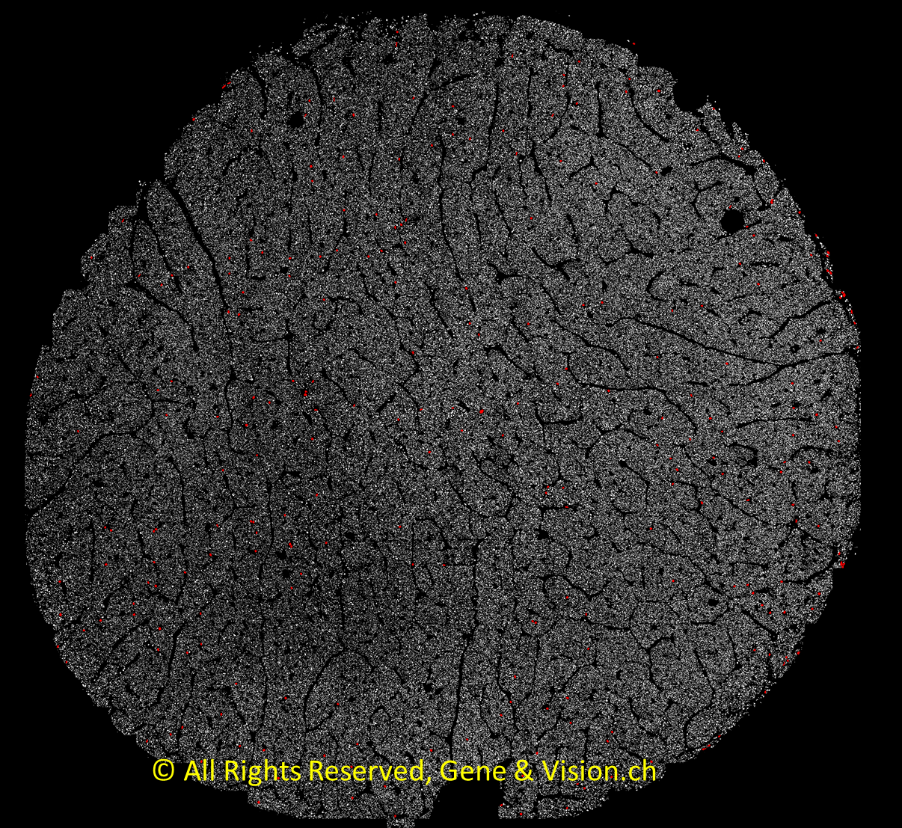

The Swift and Swallow optic nerve

We wondered how the axons of the big Ganglion Cells are topographically organized in the optic nerve. In birds, the number of optic nerve axons range from a few hundred thousand to several millions. We have developed a tool that apply a deep learning algorithm to identify and mark axons in the whole optic nerve (Figure 4).

We found that the largest axons are myelinated and clustered (Figures 5, 6). They are distributed over a discrete area which is consistent with the fact that the big Ganglion Cells from which they originate are located nearly exclusively in the temporal fovea. Large axons are distributed according to similar patterns in swallows and swifts.

In sharp contrast to the situation in swifts and swallows, there is no clustering of large axons in birds with no fovea, like, for instance, the Japanese Quail (Figure 7). In that case, the large axons are scattered over the entire surface of the optic nerve.

Conclusion and perspective

In the swifts and swallows optic nerves, there are ~300 large axons (diameters > 4 μm). They originate from the big Ganglion Cells located in the temporal fovea. These big Ganglion Cells (5-10% of all foveal Ganglion Cells) are connected via bipolar and amacrine cells to cones. They are likely to be involved in the detection of movement and orientation and could play a determinant role for the fine tuning of bird flight on the final approach to catch insect. Foveal big Ganglion Cells and their clustered large axons in the optic nerve are specific features of swifts and swallows. They could enable the fast transmission of action potential required for the needed ultra-rapid sensory-motor response. What central neurons are involved in this response and how are they organized? These are questions that we are trying to answer as we continue to develop this project.

References

- Oehme, H. (1962). Das auge von mauersegler, star und amsel. Journal of Ornithology, 103, 187–212. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01670869

- Rochon‐Duvigneaud, A. (1943). Les yeux et la vision des vertébrés. Paris, France: Masson.

- Rodrigues, T. (2023). Increased neuron density in the midbrain of a foveate bird, pigeon, results from profound change in tissue morphogenesis. Dev. Biol. 502, 77-98. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ydbio.2023.06.021

All our publications are available here.